Friday, November 28, 2008

Race and Manufacturing (reading response)

Wednesday, November 26, 2008

Creativity in the Political Economy (Reading Response)

My point in unpacking the Marxist project with regard to labor in the fashion industry is to suggest that this methodological lens is simply not enough to facilitate the kind of social change that these authors are (admirably) shooting for. It occurred to me that perhaps considering the life of the creative cycle (rather than only the manufacturing) would be another productive point of intervention. In other words, where is the site of creativity? And – because I’m convinced that it is neither stable nor residing only at the top of the food chain – how is aesthetic innovation harnessed through the division of labor? What critical lens is necessary to interrogate the flow and temporary hubs of creativity in fashion manufacture?

To be fair, Nielsen tries her hand at “creativity,” but her version is “synonymous with resourcefulness.” While this is a completely valid component of creative production, I’m proposing to look at aesthetic innovation. Robin Givhan’s essay on “ugly chic” (in “No Sweat”) is more in line with the notion of interrogating aesthetic innovation. She looks specifically at designers’ (violent) appropriation of poverty, homelessness and perhaps even drug use to create a sort of “ugly” aesthetic (poor-boy and poor-girl chic). What is rendered as “exotic poverty,” deliberately paired for obvious incongruence, on the runway is an inescapable material reality for most of the world’s population. She concludes that this branding of poverty (much like the branding of race, girl power, and class consciousness) not only de-politicizes the actual struggles of these constructs but also works to reveal that fashionable edge often relies on “the poor, resourceful masses.” While this abstraction is certainly important, it seems clear that not only is Marc Jacobs pilfering from the poverty-stricken and globalized masses, but from the exact same workers employed in his sweatshops (figuratively speaking – I don’t know for sure that he has sweatshops). Yes, designers are “mocking global poverty,” but more pointedly, they are appropriating the creativity of their very own workers. These practices, coupled with Howard Becker’s examination of the collectivity of artistic innovation (I’m thinking of his book “Art Worlds”) are, I think, instructive in beginning to examine the life of creativity in the processes of the fashion industry.

Otaku: The Japanese Nerds Stand Tall and Proud

Tuesday, November 25, 2008

Garment Worker's Center-- Shop with a Heart 2008

Shop with a Heart 2008

Fair Trade Fundraiser Dec 4th, Thursday 6pm

The Garment Worker Center is gearing up for our annual fair trade sale. We have a new site to sign up to support our event. Please check it out and share with your friends:

www.garmentworkercenter.org

Our fair trade sale, which will be on December 4th thru December 11th will give you an opportunity to buy fair trade gifts - meaning that the workers who made those items were paid properly and worked in safe environments. Part of the proceeds then help to support local garment workers in their effort to organize and stop sweatshops in LA.

There is no fair trade store in Los Angeles right now - so come to our event and buy your gifts and feel good about your purchases. We will also have our fair trade store open for a week after the reception date to give people more chances to shop.

Please join us for an evening of fair trade shopping and a very special reception honoring exiting Executive Director Kimi Lee and the Bet Tzedek Employment Rights Project.

With Kimi's departure, we enter an exciting new chapter in the future of the Garment Worker Center. We cannot continue our work without community support and we hope that you consider sponsorship to help make our fundraiser a success!

GWC: 1250 So. Los Angeles Street, Suite 213, Los Angeles, CA 90015

www.garmentworkercenter.org

Happy holiday shopping!

Sunday, November 23, 2008

Ode to Jeans

On skinny jeans: it seems everyone is in agreement that skinny jeans are manifestation of a masochist mechanism that attempts eroticize and infantilize grown women (they do, after all, look an awful lot like little girls’ leggings… all we’re missing is the matching scrunchie). I totally agree. They don’t fit anyone how they’re supposed to, they’re way too expensive for a fad, the colors make me think of ice cream, and the ankle opening might as well be a joke. Plus, the really popular ones like J Brand (I think I might have railed against the brand in class already), are pretty much made for pre-pubescent boys – the inseam zipper is like 2 inches.

That said, I have a pair of skinny jeans. Black ones. And I love them. And here’s why: utility. (Stay with me) For those of us who go back-and-forth between wearing high heels, higher heels, and flats, the same problem emerges: length of jeans. I’m convinced that it’s the industry’s way of making us purchase a million pairs of jeans (seriously, can’t they make a secretly unfolding bottom hem? Seems so simple) I know, I know, it’s a major life dilemma. But here’s the thing, the skinny jeans completely solve that problem because they can go with any heel height. Plus, you can wear old dresses that are way too short to wear as originally intended, as tops.

So, if you’re publicly shaming wearers but secretly pining for a pair, I think the trick might be in the fabric – they have to be real denim (I had to go up 2 sizes, but they fit). Not the 90% stretch kind, but the hard denim variety, with maybe only 1-2% stretch. Levi’s, Gap, Apple Bottom, and AG make good ones. Levi’s and Apple Bottoms are especially good for curves. If you’re unconvinced by the skinny, Joe’s “Muse” jeans are cut like regular pants – slightly higher rise, wider leg, and longer – and fit many different body types. And, the best part is that they go on huge sales, pretty often at Nordstrom Rack and sometimes Marshall’s.

xoxo,

Shallow

Friday, November 21, 2008

Denim advice

Deener denim - They have a bit of give (but they aren't stretch denim), so they are a bit forgiving in the hip region (although the calves are a bit tight). They are an LA company, but I have only seen them in NY, so here is the website...

http://www.deenerdenim.com/

I also recently discovered Martin + Osa's jeans...they are very forgiving, they come in different lengths and they do free alterations if needed...they might not have the cool cache of some brands, but they did have the best white denim that I could find.

Star Doll: The Ultimate Fashion Power

In researching for my last post I came across Stardoll. A site where you can dress up your favorite celebrities paper doll style in infinite wardrobes of your choosing. I created an Avril Lavigne doll using outfits from her new clothing line, Abbey Dawn. Talk about genius marketing.

Dress up Paris Hilton, Jessica Simpson and many more, but with the power to make them fashion disasters at your whim. I think I am enjoying this way too much...

Thursday, November 20, 2008

Subcultures as newer economies of re-signification.

Silverman's brilliant explication of how exhibitionism is fundamental to the constitution of male subjectivity (and not just female) resonated with my understanding of the display and valence of bodies in Mi Vida Loca. While costumes of the characters were fairly conspicuous, I was intrigued by the adornation and styling of hair, and the plethora of styles that were on display with both male as well as female characters. Perhaps, these practices could be connected with a notion of care of the self even when living within financially straitened circumstances. I am also grappling with how naming is shown to work within the dynamics of this particular class and ethnic community of Echo Park. The nature of the names adopted by the characters at one level seem to express a disaffiliation with the individual proper names of mainstream white culture and a distinctive economy of individuation; and at another, the almost incantatory reference to each other as 'our home-boy' or 'our home-girl' seems to signal an equal desire for a collective identity, a shared sense of honor and responsibility. The unique and distinctive kinds of styling and self-identification seem to emerge in starker contrast within the homogenous precincts of Burger King and McDonald's.

Avril Lavigne and the Mainstreaming of Subcultures

In reading this I was forced to re-examine my feelings on the new Avril Lavigne designed clothing line, Abbey Dawn, now available at Kohl’s. Avril Lavigne’s style has always been punk inspired, but her mainstream music and now fashion line has always been a point of contention for the the true punk rockers out there who find their power in their position outside the mainstream. This is true in general for the readings this week, subcultures can only be defined as oppositional or outside mainstream, but what happens, in the case of Avril and her clothes, when the subculture is now available for mass retail? This has been a reoccurring theme for our class this semester in terms of agency. Can one have power while operating within the established repressive order? Silverman seems to think yes. And although I was mighty tempted to buy myself an Avril Lavigne designed sweatshirt the last time I was shopping at Kohl’s with my mom, if only because her subculture style definitely fits my idea of my own relation to fashion much more than Kohl’s traditional mainstream fair, I just couldn’t do it in the end. A mass produced Avril Lavigne sweatshirt just misses the heart of the punk rock credo.

In reading this I was forced to re-examine my feelings on the new Avril Lavigne designed clothing line, Abbey Dawn, now available at Kohl’s. Avril Lavigne’s style has always been punk inspired, but her mainstream music and now fashion line has always been a point of contention for the the true punk rockers out there who find their power in their position outside the mainstream. This is true in general for the readings this week, subcultures can only be defined as oppositional or outside mainstream, but what happens, in the case of Avril and her clothes, when the subculture is now available for mass retail? This has been a reoccurring theme for our class this semester in terms of agency. Can one have power while operating within the established repressive order? Silverman seems to think yes. And although I was mighty tempted to buy myself an Avril Lavigne designed sweatshirt the last time I was shopping at Kohl’s with my mom, if only because her subculture style definitely fits my idea of my own relation to fashion much more than Kohl’s traditional mainstream fair, I just couldn’t do it in the end. A mass produced Avril Lavigne sweatshirt just misses the heart of the punk rock credo.McRobbie’s article, while interesting in its exploration of race, class, style, youth and gender as organizing principles for subcultures was tremendously confusing to me having not read the 2 texts she continually references. She assumes a definition of mainstream that is unspoken and can only be understood as whatever she doesn’t define as a subculture. Example: “It has always been on the street that most subcultural activity takes place” (29). And so the leap is that mainstream does not take place on the streets. But if it doesn’t rely on the streets for visibility, than where does mainstream visibility lie? Malls, media? I was having continual problems locating what she considers mainstream in relation to her extremely varied examples of subcultures which seemed to be loosely defined as anything “other.” Maybe I just missed something?

I don’t really have anything concrete to say on the Fergosa article other than that I found her anecdotal method of address to be refreshing and easy to follow. Ditto for the Acker interview. The “On Thrifting” article did not work for me. Its mix of academic and colloquial language and reliance on personal experience was frustrating for me. The exploration of value coding was insightful and useful, but the tips and the totalizing generalizations of thrift shoppers as a whole distracted me from the value of the authors’ other arguments. I thought this article would be my favorite to read since it is in “Hop on Pop” edited by Jenkins and Tara, but man I had to put it down and come back to it several times. Am I crazy for responding in this way?

I would argue that women (or people in general although I will use women here) do not write their fashion histories out of existence however. Most women build on those histories as their styles and wardrobes evolve but are not constantly erased as they are on the main cultural and economic stage of fashion. I think women develop complex affinities for individual fashions, and particularly for individual garments.

The archetype of the fashionista who "never wears anything twice" and whose life is a revolving door of looks and garments is clearly very different from the average consumer, and I think for most, not at all the ideal. I think for many women, a garment that fits well and makes them feel good is a rare find and becomes like a friend. They develop an intimate tactile and aesthetic relationship with it and the garment often takes on the character or value of the experiences that occur while she is in it. Unlike the fashion industry ideal in which the closet is a bottomless pit of newness and surprise, the closet of most women is more like a library of cherished possibilities, many endowed with meaning and value beyond their surfaces.

Subcultures and domesticity

As for the Acker article, because it is an interview, it is not as coherently organized. To be sure, her comments on domesticity are tangential to her broader comments about a woman’s relationship to her own body’s sites of pleasure/pain/fantasy/play. But, perhaps this is why these moments struck me. When she challenges the misconception that women who want to be spanked position themselves submissively, she moves into an argument about suburban women who really “are” submissive: “Actually submissive women freak me out; I like women who know what they’re doing... I guess everybody makes a choice, somewhere down the line: that they’re going to abide by society’s rules and hide in their nice suburban house and do what they’re told... and maybe, just maybe, they’ll be ‘safe.’” To me, this seems uncharacteristically uncomplicated -- as are her comments about plastic surgery -- but perhaps signals a particular feminist discourse circulating at the time (1991). I mean what would Lynn Spigel say? Or maybe Spigel’s comments about post-War domesticity and post-Reagan domesticity would be different. I digress-- more importantly, Acker positions the woman contained in her suburban house as a foil for those women who are more polymorphous(ly perverse), adventurous, “true to themselves” and not to society’s norms. But, who’s to say that these women aren’t finding their own radical pleasures and getting kinky somewhere behind or on those well-manicured lawns when no one is looking? So, while Acker points in some way to the existence of sexual subcultures that are inclusive of women (orgies in her room, BDSM communities, etc.), she does so by re-inscribing the domestic as something separated from the vibrant worlds lived “in the streets.”

Fregoso’s comments about domesticity versus the streets perhaps offers the most textured account. She begins by re-constructing for us the image of the pachuco, whose immediate familiarity already offers evidence of her point. Chicano urban style has been representationally reserved for the province of men, in spite of the vast presence of women in the actual barrios. If anyone went to see the Cheech Marin collection at the LACMA this summer can attest to just how masculine and heterosexual Chicano art of the 1960s and 1970s was, though it was a really impressive show. Needless to say, the feminist absence in spite of its historical importance, with the exception of a few Diane Gamboa pieces, was striking. Fregoso, like McRobbie, critiques the gendered street/domestic divide, though she addresses it more specifically as it cuts across with race. The body of the pachuca, and the chola, ruptured these spatial divisions; she “refused to be confined by domesticity” (75). However, she returns to these "domestic refusals" in her analysis of Mi Vida Loca. One of her primary complaints with the film is its construction of the dysfunctional Latina family in spite of the crucial importance that the extended system of support that the family provides in the barrio.

I know this post was all over the place. I just really wanted to zone in on the trope of domesticity, because it offers such an interesting contrast to last week's conversations about domestic sitcoms.

8 Things I Hate about "Pretty in Pink"

I'm sorry for being so vocal (and annoying) this week, but I just couldn't resist this. I’m going to say it: I hate and have always hated Pretty in Pink. And here's why:

"Thrift Store Chic"

Although incredibly spot on, I do think that "On Thrifting" needs an update. While reading it I started thinking about how the barriers between first and second order forms of clothing are being increasingly blurred. Retail stores like Urban Outfitters and Top Shop, and designers like Marc Jacobs and Chloe are designing clothes that look like they are from a thrift store but with a first-order (and often very extravagant) price-tag! Scouring the net for examples of high-end thrift inspired clothes, I stumbled upon an article from The Independent about Chloe’s spring 2002 collection titled “Thrift Shop Chic at it’s Finest.” Here are some quotes: “Sweaters looked as if they had been worn and washed for decades” and “It was thrift shop chic at its finest and at designer prices.” Is it just me, or is that counter-intuitive? This is taking value-coding to a whole new level by assigning absurdly high prices to clothes that are replicas of clothes that cost a few dollars!

I prophesize that if the grimness of our economic times continues, thrift will not only become more and more popular, but also more and more necessary. In fact, my prophecy is already a reality, as mainstream merchants are struggling, many secondhand stores are posting record sales, up 30% overall from a year ago. So what happens to its cultural and political message when thrift store dress is subsumed by mainstream culture?

Reading Response: Subcultures

Style Culture and Female Masculinity (reading/screening response)

McRobbie briefly discusses the spatial marginalization of working class women embedded in British subculture, a preview to Fregoso’s extended engagement with the politics of public visibility that governs the Chuca-Homegirl-Chola’s subcultural style. Fregoso also bemoans the invisibility of the Pachuca within Chicano and mainstream white media culture, performing a similar criticism of the bias seen through films that attempt to recreate Chicano gang life through exclusively male perspectives and spaces. Through praise for Mi Vida Loca’s complication of the public/private dichotomy that often becomes normalized via “gangxploitation” films, Fregoso recognizes the importance of homosocial spaces to the articulation of Homegirl-Pachuca-Chola self-reliance. While Fregoso recognizes the potential for homoeroticism (not quite homosexuality) as a component of the transgressive, oppositional politics in Homegirl social figurations, however, how can we read across their style culture and affect forms of female masculinity that complicate the binaristic virgen/malinche formation that seems to be rooted in forms of femininity?

Subculture and the case for Kamikaze Girls (2005)

Kamikaze Girls is a coming-of-age story of two girls, Momoko and Ichigo. The film begins with Momoko being hit by a truck and much of the film is seen in flashback. Although I am describing the film as a coming-of-age story, the film primarily negotiates the development and drama between the two young women through their respective styles. Momoko is obsessed with the store, Baby the stars shine bright (which sells her “Lolita-style” dresses and bonnets) and Ichigo is a bad-ass biker who is described as a “Yanki.”

Their friendship begins when Momoko needs to figure out how to make money so that she can continue to buy clothes from Baby the stars shine bright (http://www.babyssb.co.jp/), and she begins to sell some of the backstock of her fathers “Versashe” and “Universal Stadium Versashe” clothing. Although these two young women have very different styles and social groups (Momoko doesn’t actually have any friends), they come together and become friends when Ichigo arrives at Momoko’s house to buy some Versashe clothing.

In many ways this film is only taking up the issue of subcultural style (as a set of codes), which allows it to avoid some of the complexities of group dynamics (unlike Mi Vida Loca). Despite the fact that the film bypasses some of the sexual politics and ramifications of style choices (the Lolita look starts to get eerie),

there is a very conscious engagement in the film with the way in which women engage with consumer choices (highlighting a female prerogative in style) and the construction of their styles. In the film the designer from Baby the stars shine bright calls Momoko in an attempt to employ her as a designer for the company after she finishes high school. Instead of accepting the job, Momoko decides that she does not want to make the clothing that she loves because it will eliminate the fantasy of the clothing. While the translation of style into a job (which allows her to actively participate in the system of capital) seems like a way out (or progressive development), Momoko’s decision signals that there is more to her consumer choices and style than simply buying and/or making clothing. For Ichigo, style becomes a way to connect her to her female biker gang, but also to Momoko and Kimi (the leader of the gang) through Momoko’s embroidery on her clothing. On the other hand, Momoko’s style becomes a way to alienate her from both her peers and the community at large (as none of them understand why she can’t go to the local supermarket and buy what they wear). In the case of Momoko, this hyperfeminity provides a means to distance herself from teenage heterosexual desire (at least in the narrative world of the film) and exist in a fantasy world (although there seem to be a few undeveloped lesbian undertones between Momoko and Ichigo). Ultimately, why I think that this film fits in with a discussion of McRobbie's "Settling Accounts with Subcultures" is that it takes up issues of female style both in the context of female relationships, but also within a female engagement with style, consumer choices and to a particular extent, elements of DIY (via Momoko's embroidery skills).

Eat your heart out Rachel Maddow

I was sifting through photos because I wanted to write more of a personal post this week and include some pics, and happened to run into this. So, here's my prom queer photo. Anyone else care to follow my lead in radical narcissist solidarity? And, more importantly, can someone tell me what in god's name would possess me to wear closed toe heels with a full length dress?

Wednesday, November 19, 2008

Iona!

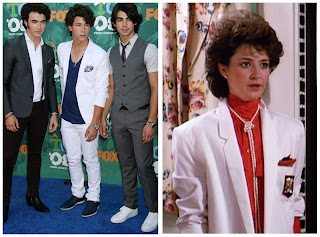

Her transformation from this:

To this:

Is tragic and definitely something worth talking about in terms of subcultural female style. On a side note, to explain the picture of the Jonas brothers, I had the most difficult time finding the image of Iona in a suit and the only one I could find was on a blog comparing her look to the Jonas brothers. At first I thought about cropping it, but then I thought this could provide for even more fascinating conversation.

Is tragic and definitely something worth talking about in terms of subcultural female style. On a side note, to explain the picture of the Jonas brothers, I had the most difficult time finding the image of Iona in a suit and the only one I could find was on a blog comparing her look to the Jonas brothers. At first I thought about cropping it, but then I thought this could provide for even more fascinating conversation.

Monday, November 17, 2008

Michelle Obama and Vogue

Any votes as to what she should wear?

Sunday, November 16, 2008

Sidewalk Aporia

Friday, November 14, 2008

Gossip Girl clothing blogs

http://www.gossipgirlcloset.com/

Thursday, November 13, 2008

Labor, technology and markets - thinking through some of the connections.

I am also wondering what the co-existence of resistant readings of the televisual narratives (seeking to co-opt viewers to the ideologies of self-realization) as well as consumption and enjoyment of the same may ultimately amount to. I am reminded here of the reference to Modleski's idea of the intellectual pleasure of 'getting the joke' but not laughing with it, that had come up in an essay we read a few weeks ago, as one model of ambivalent reception. I am also thinking whether the presentation of particular kinds of gender steriotypes (the inept husband and the tolerant, thrifty wife; or the sardonic husband and the twittering, zero financial quotient wife) all of whom seem to still be enjoying an after-life, may also not be read as articulating dissatisfaction with existing codes of pecuniary responsibleness and compulsions while also enacting dysfunctionalities.

Packing Heat

Consumption and Transgression (Reading Response)

George Lipsitz contends that 1950s television programs, particularly urban working class situation comedies, put greater emphasis on nuclear families and less on extended kinship identities and ethnicity than their radio predecessors. In post-WWII America, these situation comedies served as a means of ideological legitimation for a fundamental revolution in economic, social and cultural life. The origins of television’s drive toward consumerism rests with government-induced subsidies and incentives to promote consumerism via post-war television narratives. The result of this consumer consumption fetishism included greater home ownership by the working class to go along with greater credit debt. Television narratives placed greater emphasis on values placed on the ability to consume. It is interesting to note that for homemakers (most of whom in the 1950s were women), the gains in product/food technology (which intuitively would have meant less time spent doing housework), whether it meant the technological advancement in processing food or electric appliances—were cancelled out by the consumer ads and mass marketing of consumer culture that Lipsitz concludes promulgated upgraded standards of cleanliness and expanded desires of material consumption which resulted in a zero net gain in terms of hours doing housework. This trend of zero net or even negative net gain in terms of housework or leisure time has continued since the 1950s, as working time has actually lengthened (even with greater techonological/communication advances since the 1950s), partly in response to satisfy desires for material goods in an ever-expanding consumer culture.

Shows like Life with Luigi and Amos and Andy reflected the narrative unities involving individual material consumption aspirations as if such desires and subsequent consumption was transgressive—that is, you can transcend class, status and race through consumption of goods. As earlier readings from Berry point out, particular fashion lines enabled working class women to ‘elevate’ their own class positions through the consumption of certain fashion lines. Similarly, these urban television sit-coms, with their ethnic sensibility, also presented marginalized groups with the romantic ideas of transgression and collectivity through material consumption. Whether you purchased homes, cars and other electronic appliances on credit, these sit-coms promoted the idea that consumption amounted to ethnic and class transgression. I think today’s consumer culture, through celebrity tabloid periodicals or shows like ‘Sex and City’ have continued to promote this idea of ‘blurring the lines’ of mass and high culture via consumption. Nobody knows you are buying a Birken bag with an installment payment plan. However, the purchasing of goods beyond your means is, as ‘Molly Goldberg’ states “the American way.”

Lipsitz, White and The Honeymooners

I thought it interesting then how the particular episode of “The Honeymooners” we watched kind of moves between these two arguments in certain ways. For one, as Lipsitz notes, Alice Kramden is constructed as the practical, frugal character while Ralph is constantly getting himself into trouble with his irresponsible spending habits. In “Better Living Through TV,” Ralph gets involved in a get rich quick scheme, as he stumbles upon a bunch of all-in-one kitchen gadgets that he wants to sell (I want one, though I could do without the corn remover). In order to move his product, however, he goes onto none-other-than a home shopping show, pointing to obvious existence of precursors to networks like the Home Shopping Network. Most interstingly, it seems like the Honeymooners in fact ironizes, nay critiques, the class underpinnings of home shopping TV. In keeping with the conventions of this subgenre, Ralph is made to appear as the class fool as he believes he is going to make a ton of money but then freezes on live TV. But his antics also the expose the cracks in how these shows might inflate the value of its products - I think the object breaks on camera (this might have been a blooper), he can’t core the apple, etc. So the scenario sort of points to an America that has shifted to a consumerist economy where there might be a market of “working-class dupes” who would be willing to purchase such products off of television. But it doesn't critique the dupes, but the production of these working class desires, embodied by the figure of Ralph.

My Own Producer/Consumer Identity and Raining Shoes

I must say though, that 2 weeks ago, when my car was broken into and attempted stolen, I felt completely helpless and just stunned that someone would personally attack me in such a way. I was powerless and had no recourse to recover my stolen property. What I did next, surprised me. I spent 2 hours making, with my hands, a crazy wired futuristic gadget for my film shoot. When everything spun out of control for me, it was my place as a producer, actually having the satisfaction of creating something tangible, that exists in the world, that I could feel (rather painfully) come to life of my own volition, that gave me back that sense of control I needed. In this moment, it was my role as a producer as opposed to a consumer that gave me the greatest sense of power and control over my life. So, are we really so dependent on consumerism for our sense of identity and worth as these articles suggest?

Of course, given what bits of my own research that I have presented so far in class, Berry’s article about “mass customization” and micromarketing on the internet was fascinating. The-N website is already tracking consumer opinion by having kids post on threads and vote in polls and rewarding them with “creds” for their time, which then, in turn, encourages virtual spending. Sites like Second Life, further blur production/consumption because you can produce virtual objects and then sell them, within the realm of the game for real money. Whether you are playing with an in-game/site currency or real money, virtual consumerism is the new landscape.

Ok, I have to derail for a second because I just looked up at my muted TV and caught a car commercial where it was raining shoes. The point of the commercial is that you should buy a giant SUV because you never know when you will need the extra space Like, for example, when it rains shoes and you, as a woman consumer, are literally in heaven stuffing as many shoes as you possibly can in the back of your brand new Chevy Traverse.

This commercial speaks volumes to what all of the articles danced around, Haralovich, Rabinovitz, White and Lipsitz in particular are specifically speaking of the woman as a consumer. The notion of the male consumer is almost entirely absent. The one male in the commercial is eating a hot dog and looking at all the rabid, shoe-mongering women as if they were aliens from mars. Vapid consumerism is feminine and always has been, a silly, yet necessary past-time.

Rewriting Domestic Consumption (Reading Response)

Although I’m not convinced that the extensive contrasts between Leave it to Beaver and Father Knows Best were any more than just amusing (are these the kinds of differences that make a difference?), Haralovich’s piece seems a good establishment of the social context in which TV crystallized the marriage between gendered domesticity and consumption. The next natural step, it seems, would be to examine how these same images are now nostalgically deployed to assert the kind of homogeneous, nationalist past that early TV and radio originally worked towards. Now sold as kitsch and as a sort of ironic hyper-history in Technicolor, these representations are still doing the cultural work of nationhood – their revival re-imagines and effectively, rewrites a collective past, sanctioning a move into the future, a move severed and therefore untroubled by histories of heterosexism, racism, and gender binaries. The whole notion of “fragmenting demand” (Berry), as assumingly conducive to our fluid, fragmented identities (as we’re constantly told anyway), just begs for a mention of Frederic Jameson and his (albeit incredibly pessimistic) definition of postmodernity. This fragmentation, fueled by capitalist consumption and its twin promises of cultural innovation (Jameson says it’s really all pastiche) and personalization undermine coalition and progressive social change. Berry cites the Dell computer website to suggest that some product customization can sometimes be beneficial for consumers. Sure, but at what cost? What no one in the readings seems to consider are the double-bind illusions of choice and empowerment that niche marketing seamlessly accomplishes and the bearing this state of content has on political work.

Haralovich does a good job of situating the suburban home and reducing it to all of its consumable parts. Since white flight was so instrumental in making the Cleavers’ dream a reality, I think it would be a worthwhile project to study how the marketing of gendered domesticity is responding to the current reversal of white flight. There were several articles this summer that boldly proclaimed the “end to white flight,” citing the kind of population shifts across major cosmopolitan areas across the U.S. that would make even the eager supporter of gentrification cringe.

Regarding customer management, Berry notes that “the most basic classifications of women began with three 'fundamental' types (dramatic, ingénue, and athletic).” It would be interesting to catalogue the current “fundamental types” and see to what an extent each of these categories has become more overtly sexualized. In other words, what type of sexual subjectivity has been attributed to “types” in light of third-wave and post-feminism’s (doomed, in my opinion) reclaiming of the body as a space for agency and the right to raunchiness. Is the athlete really the sexy athlete with the panty endorsement deal and is the ingénue more of a self-aware and strategic Lolita?

Working Class Taste Labor (reading response)

We can see the reincarnation, and even reinvigoration, of the early 1950s urban family sitcoms, that Lipsitz focuses on, and their appeals to working class taste cultures through the Home Shopping Network strategies of product marketing that White discusses. Here the viewer’s domestic space becomes the staging ground for their own productive and actualized forms of consumption, an engagement with the products and people seen onscreen. What is particularly interesting (I admit to my own outsider fascination with how these networks function) about White’s discussion is how she critiques the “conventional denigratory paradigms”(91) that characterize feminine consumer participation as precisely lacking the proper distance required to discern the “real” worth behind a product and its promotion. Even though White never engages them, this echoes some of the psychoanalytic feminist theories we encountered earlier (primarily Doane), but would position them in way that ascribes to them a similar level of condescension and derision.

Some questions are raised in relation to White’s work that might help us expand upon the ideas of the female viewer and televisual modes of consumption. As White comments on the prevalence of testimonial callers on HSN, one might question how much the labor of the consumer/viewer gets factored into the pedagogical function of online and televisual forms of marketing and commodification. How then, as these viewer-consumers are participating in the construction of these televisual marketing environments, are they also actively cultivating a larger taste culture?

Addiction, Obsession, and Compulsion

I really liked the way in which you could trace through our readings for this week a trajectory of the creation and exponential growth of the commodity consumer. They most definitely helped contribute to my understanding of today's economy (and sadly to my own understanding of myself as a consumer).

'Celebrity hosts inject glamour and credibility into the world of TV home shopping'

"Raquel Welch wigs"?

"Raquel Welch wigs"?Spectators, Consumers, and Users

The articles for this week all seem to circulate around several different historically specific models of the spectator-consumer, all of which trouble the idea that television viewers are merely mindless dupes ready and willing to buy anything advertised (although maybe Rabinovitz does suggest this), but at the same time explicitly attempt to negotiate the way in which spectators have been figured as consumers. While none of these articles explicitly take up the issue of the “spectator” vs. the “consumer,” these articles do seem to willingly collapse the two, or at the very least they recognize that there is an industrial rationale for figuring the spectator as consumer that cannot be ignored. Haralovich situates the spectator-consumer against a specific historical context of market research and suburban development, Lipsitz discusses the role of ethnic sitcoms as modes of working out consumer insecurities (through an acknowledgement of the past and simultaneous rewriting of the past), Rabinovitz presents a view on soap opera weddings that focuses on the spectator as consumer rather than the hypothetical, idealized spectator, White looks for a place to locate spectatorial pleasure within the Home Shopping Network, and Berry traces the history (the discussion of make-up on p. 57 was very familiar….) of the personalized product while questioning the contemporary consumer’s excitement to give personal purchasing and preference (or fingerprint?) information. In many ways I think that this is a very appropriate set of readings as we move forward in class to discuss certain types of new media technology, since some of these ideas about how the spectator and consumer become collapsed (fairly easily and gleefully), seem to resonate strongly with the ways in which “user” and “consumer” have been and can be collapsed (I am thinking particularly about the introduction to Convergence Culture here). In some ways I think Lipsitz is really working through this tension at the end of his article by asserting the importance of a reconnection with history, and he seems to be open to a kind of resistance that seems to be shut off in Rabinovitz’s article on soap opera weddings. In some ways I found the title, “Soap opera bridal fantasies” to be a bit misleading. Whereas I understand Rabinovitz’s maneuver toward focusing on “real life” consumers (as the spectator), rather than an idealized spectator that can invest in the way in which soap operas interrogate the process of marriage (rather than accept it as an end), her conclusion about the disappointment that inevitably ensues when women try to recreate the soap opera wedding, seems to reinforce an idea of the spectator as cultural dupe in a mode that is both unsettling and seems to be only vaguely substantiated by anecdotes (although I am willing to take criticisms that I am being naïve here….).

Realism and Excess

If there is some level of collapse between spectator and consumer, Mary Beth Haralovich’s article, “Sit-coms and Suburbs: Positioning the 1950s Homemaker” presents a historical argument that combines information on growing changes and developments in market research, the growth of the consumer product industry and the policies and politics of urban and suburban planning in the 1950s to illustrate how Father Knows Best and Leave it to Beaver reproduce the values and policies of the time. The result is an argument that relies on the way in which both the articulation of space and a detailed mise-en-scene reproduce the division of labor and gender roles within the 1950s family (although it also seems like the “open plan” that she discusses seems to reek of some kind of family surveillance system). While Haralovich convincingly details the way in which the homes of the Andersons and the Cleavers produce an idealized suburban lifestyle, she also briefly mentions Robert Woods Kennedy’s idea that housing design should emphasize female sexuality, a point which Haralovich discusses through costume design. At several points within the semester we have talked about the way in which both mise-en-scene and costume can produce a degree of excess (that triggers or generates alternate forms of identification). Thus if these shows attempt to produce a spectatorial engagement with the home life, it seems to me that the presence of appliances and the suburban environment is producing a kind of excess that is the fantasy of more free time for housewives/homemakers. Admittedly part of my question here comes from the fact that none of these articles take up the particularly messy issue of integrating television and appliances within the family home (by the time I started the Lipsitz article I began to feel like I should have also been reading Spigel’s chapter “Women’s Work” for this week).

Wednesday, November 12, 2008

Manic Pixie Dream Girl

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

Stylista host Anne Slowey's Food Diary

(ETA: This could be triggering for anyone who suffers/has suffered from an eating disorder. Some of the comments may take a toll on your Sanity Watchers points.)

Elyse Sewell

Which is a verbose way of saying, click the title of this post. You've got to see this shot. It's totally my new computer wallpaper.

Monday, November 10, 2008

1950s television episodes and Lipsitz

As I was reading Lipsitz, I found it helpful that he provides numerous examples of how different shows work out a variety of different consumer insecurities (which stem from post-Depression anxiety). His example of Mama on p.101 seems to be a particularly effective example of “putting the borrowed moral capital of the past at the service of the values of the present.” While Lipsitz is focusing on the ways in which historical memory is reworked in television to serve the needs of capital, it seems to me that the episode of The Honeymooners screened in class works out consumer insecurities in a different fashion (one which particularly resonates with Mimi White’s chapter on the Home Shopping Network). Therefore, if Lipsitz is talking about the role of history in the construction of the consumer, is there a way that we can talk about how taste functions within these shows as well? The Honeymooners episode screened in class seems to set up a binary between “good” consumer objects (tv, washing machine, vacuum – all the objects that cannot be obtained) versus the “bad” object of the 85-in-1 corn remover/can opener/paring knife/thingy. While the humor from the episode is derived from the viewer’s ability to clearly identify the uselessness of the item, which in turn validates the utility of items such as the television, vacuum, etc and the viewer’s role as discerning consumer.

Lastly, Lipsitz also discusses the way in which the narrative of many of these shows can often be resolved by consumer products (p.81). My comment on narrative seems to depart a bit from this analysis, but I found it curious that in both Make Room for Daddy and The Burns and Allen show that the narrative action seemed to be primarily driven by the female actions and decisions. As I said before, I have very little frame of reference for 1950s television, but it seemed curious to me that the narrative was primarily driven by the mother.

Sunday, November 9, 2008

Michelle Obama's real world style

And, Nancy Reagan was a size 2??

Friday, November 7, 2008

Visceral Impressions: The Fashion-Music Discussion + Angela Davis

I have been ruminating recently on the relationship between music and fashion that appeared here on the blog a few weeks ago. I think that music and fashion share some interesting commonalities in the ways that they are recognized and consumed. Each of them is made up of a host of minute details—notes, sounds, instruments, fibers, fabrics and textures—but each is also very frequently processed at a macro level of mood or tone without the consumer’s (in this case meaning anyone encountering and visually or aurally consuming the music or fashion in question… “perceiver” might be a more suitable word) attention being paid to the often significant details of the article's construction.

While it might easily be argued that any media or art may be approached with varying levels of attention to detail, I would contend that fashion and music (among other possible social or artistic projects I’m not thinking of right now) are uniquely consumable and recognizable from a distance without enjoyment being predicated on notice and processing of said detail (unlike, for example, a story or film). The style of a given ensemble is most frequently perceived as a hazy combination of colors and shapes, just as a piece of music is initially a collection of sounds. Each has a specific emotional character. Without further attention paid, they remain just those hazy constructions in a person’s consciousness, but this lack of attention to detail does not mean that the article has not been enjoyed. I think consumers frequently have a very strong visceral sense of a particular fashion (be it an entire style or a specific outfit) or song, without being able to recall or describe many of the components of its construction. When people do attempt to describe the qualities of something with which they have come in contact, they often do so in terms of comparisons with other styles, outfits, pieces or songs that have a similar qualities or evoke a like feeling. It is often only at the level of emulation or connoisseurship that a consumer actually invests their attention in the individual components that actually make up the feeling of a particular presentation. I think this experience is one in which the consumer processes the form of an artifact and then may or may not ever proceed to engage with the details that create the individual artifact’s content.

In some ways I think that this relates to Angela Davis’s discussion of her experience as a photographic subject. Above, I am suggesting that the impression of a style is essentially that style for viewers that do not undergo further investigation. The photograph compounds this issue, as it further distances the article from its detail and context. This impression of an impression becomes permanently encapsulated in the two-dimensional image. Davis’s photographs divorce her from the content of both her physical style and her larger persona in general, reducing her to a synecdoche of her form—the Afro. Like many cultural or historical figures, she remains a vague impression to the uniformed or uninitiated. The strikingness of her image may actually impede consumer’s inquiry and understanding of her cultural meaning, as her form, via the photographs, is so richly endowed with impressions and associations, that they are assumed to be that image's content.

Thursday, November 6, 2008

Nostalgia and black style politics

I want to map some of the temporal threads that run through Mercer, Davis and hooks’ work, as I am fascinated by how nostalgia and romanticism centrally function in their configurations. And, I think it’s an important point of convergence between these articles.

Angela Davis offers a personal account of how her images, which have been used by the FBI to criminalize her and by black cultural movements to heroize her, have recently circulated as emblems of style. She points to how her subjectivity and her political work have been conflated with the Afro, attributing this remarkably stubborn association to a visual commodity culture that is more invested in shaping the criteria for fashion, or more specifically, black fashion (she refers largely to a spread in Vibe magazine), than repossessing the political histories of how these photographs circulated in the first place. Davis, of course, holds an ambivalent relationship to these recent trends. She notes, “The unprecedented contemporary circulation of photographic and filmic images of African Americans has multiple and contradictory implications,” as they “promise the visual memory of older and departed generations” but faces the “danger that this historical memory may become ahistorical and apolitical” (38). She then borrows from John Berger’s About Looking to note the problems and possibilities of photography: the photograph can either become a part of everyday historiographic practice, a ‘living context,’ or be petrified as ‘arrested moments,’ incapable of being laced into present. Indeed, Davis understandably bemoans the nostalgic function, the temporal freezing, performed by the dissemination of her images in contemporary fashion magazines, as her Afro-donning image becomes paralyzed as an empty sign or artifact and ignores the political heft they carried in speaking on behalf of the number of black women who were persecuted and harassed by law enforcement for also wearing their hair big as well. But, Davis hardly calls for a return to the past; rather she calls for ‘strategies of engagement’ with these types of historical images in order to disarticulate romanticized attachments to once politicized style choices, like the Afro.

bell hooks’ chapter moves between an address of erotic desire for the racialized subject and the commodity desire or fetishism for the Other, which for her are linked. Central to her argument is the notion of ‘imperialist nostalgia,’ which ‘takes the form of reenacting and reritualizing in different ways the imperialist, colonizing journey as narrative fantasy of power and desire, of seduction by the Other” (25). In other words, the Other, for the desiring white subject, embodies the ‘primitivism,’ the ‘exoticism’ and ‘wildness’ that was supposed to be supplanted by modernity and imperialism. This temporal loss is recovered by the white subject’s consumption of the racialized body, which enacts itself not in the form of suppression, as it once was before, but through a supposedly exonerating desire for diversity and pluralism. This nostalgic function also accounts for a resurgence and commodification of black nationalism, a ‘fantasy of Otherness that reduces protest to spectacle and stimulates even greater longing for the primitive’ (33). Thus, hooks and Davis share a fundamental mistrust of these historical evacuations of black political culture of the 1960s.

Mercer, of course, offers a more nuanced take on black style politics, paying particularly close attention to black hair in the 1950s and 1960s. He refutes the association of the Afro and dreadlocks with the natural blackness, carefully articulating the ways in which these hairstyles required meticulous manipulation and maintenance. Rather, these hairstyles’ connotative links to ‘the natural’ functioned symbolically as ‘strategic contestations’ against European aesthetics of ‘artifice’ and beauty. That is, in order to be strategic, the Afro had to be defined against the associations of beauty with whiteness; in true post-structural style, Mercer moves away from strict binaries and reminds that there is a certain ‘western inheritance’ that comes with the ‘natural’ written into the significations made by the Afro. However, what is particularly interesting and useful in Mercer’s article, in my opinion, is the way he points out the nostalgic constructions of black style politics of the 1960s. The Afro and dreadlocks were imagined to hold historical roots in Africa. These connections were indeed ‘strategic’ as well. There were no actual connections between these hairstyles and African culture; the Afro and deadlocks would actually most likely read in Africa as distinctly first world. So, I think that this particular reading is an important one to make because it allows for a complication of the more blanketed argument about the commodity fetishism of black style politics made by hooks and Davis. Although, it would have been nice for Mercer to pose some readings about black women's hair. He seems to focus more on black male hair styles.